Ear infections

Highlights

Ear Infections

Middle ear (otitis media) infections are very common in young children. They include:

- Acute otitis media (AOM) is an inflammation caused by bacteria that travel to the middle ear from fluid trapped in the Eustachian tube. Children with AOM exhibit signs of an ear infection including pain, fever, and tugging at the ear.

- Otitis media with effusion (OME) refers to fluid that accumulates in the middle ear without obvious signs of infection. OME usually produces no symptoms, but some children will have difficulty hearing or complain of “plugged up” ears.

Prevention

Preventing colds and influenza (“flu”) is the best way to prevent ear infections. Make sure children wash their hands frequently and receive an influenza vaccine annually. The pneumococcal vaccine is also very helpful for preventing ear infections. No one should smoke around children, since exposure to second-hand tobacco smoke can increase the risk for middle ear infections.

Pneumococcal Vaccine

Prevnar 13 is a new pneumococcal conjugate vaccine that protects against more strains of disease-causing bacteria than its predecessor. The vaccine is specifically approved to help prevent invasive pneumococcal disease and otitis media. The recommended immunization schedule is the same as the older version, with four doses, one given at 2, 4, 6, and 12 - 15 months of age.

Treatment

- Antibiotics are effective treatment for acute otitis media. However, many ear infections resolve without antibiotic treatment.

- For most children with AOM, doctors recommend waiting 48 - 72 hours before prescribing antibiotics. However, children younger than 6 months should receive immediate antibiotic treatment. Parents can give children 6 months and older ibuprofen or acetaminophen to help relieve pain.

- Antibiotics are not helpful for most cases of OME. Doctors usually monitor children with OME for 3 months to see if their condition improves. Some children with hearing loss and developmental problems may eventually need surgery. Inserting tubes into the ear drum (tympanostomy) is the usual surgery for this problem.

Introduction

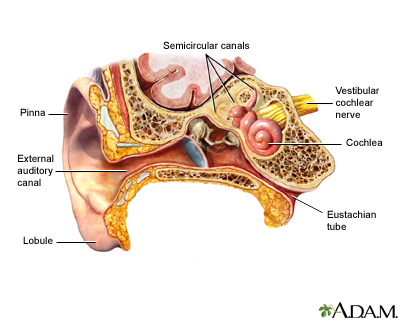

The ear is the organ of hearing and balance. It has three parts: the outer, middle, and inner ear.

- The outer ear collects sound waves, which move through the ear canal to the tympanic membrane, commonly called the eardrum.

- When incoming sound waves strike the tympanic membrane, it vibrates like a drum, and converts the sound waves into mechanical energy.

- This energy echoes through the middle ear. The middle ear is a complex structure filled with air that surrounds a chain of three tiny bones. These bones vibrate to the rhythm of the eardrum and pass the sound waves on to the inner ear.

- The inner ear is filled with fluid. Here, hair-like structures stimulate nerves to change sound waves into electrochemical impulses that are carried to the brain, which senses these impulses as sounds.

- The inner ear also contains three semi-circular canals that function as the body's gyroscope, regulating balance.

- The Eustachian tube, an important structure in the ear, runs from the middle ear to the passages behind the nose and the upper part of the throat. This tube helps equalizes the air pressure in the middle ear to the outside air pressure. Problems here are primary factors in most cases of ear infection.

Middle Ear Infections (Otitis Media) in Children

Acute Otitis Media (AOM). An inflammation in the middle ear is known as "otitis media." AOM is a middle ear infection caused by bacteria that has traveled to the middle ear from fluid build-up in the Eustachian tube. AOM may develop during or after a cold or the flu.

- Middle ear infections are extremely common in children, but they are infrequent in adults.

- In children, ear infections often recur, particularly if they first develop in early infancy.

Otitis Media with Effusion (OME). This condition occurs when fluid, called an effusion, becomes trapped behind the eardrum in one or both ears, even when there is no infection. In chronic and severe cases, the fluid is very sticky and is commonly called "glue ear."

- OME is usually not painful. Sometimes the only clue that it is present is a feeling of stuffiness in the ears, which can feel like "being under water."

- It may impair children's hearing.

- Children who are susceptible to OME can have frequent episodes for more than half of their first 3 years of life.

- Most episodes will resolve within 3 months, but 30 - 40% of children may have recurrent episodes. Only 5 - 10% of episodes last longer than 1 year.

Chronic Otitis Media. This condition refers to persistent fluid behind the tympanic membrane without any infection present. It is called chronic suppurative otitis media when there is persistent inflammation in the middle ear or mastoids (the rounded bone just behind the ear), or chronic rupture of the eardrum with drainage.

Other Types of Ear Infections

Swimmer’s Ear (Acute Otitis Externa). Acute otitis externa is an inflammation or infection of the outer ear and ear canal. It can be triggered by water that gets trapped in the ear. The trapped water can cause bacteria and fungi to breed. Otitis externa can also be precipitated by overly aggressively scratching or cleaning of ears or when an object gets stuck in the ears.

Otitis externa should be treated with topical antibiotics. For pain relief, over-the-counter remedies such as acetaminophen or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (such as ibuprofen) usually help. With eardrops, most cases will clear up within 2 - 3 days.

Causes

Acute otitis media (middle ear infection) is usually due to a combination of factors that increase susceptibility to bacterial and viral infections in the middle ear. The primary setting for middle ear infections is in a child's Eustachian tube, which runs from the middle ear to the nose and upper throat. The Eustachian tube is shorter and narrower in children than adults, and more vulnerable to blockage. It is also more horizontal in younger children and therefore does not drain as well

Infections

Bacteria. Many bacteria normally thrive in the passages of the nose and throat. Most are not harmful. However, certain types of bacteria are the primary causes of acute otitis media (AOM). They are detected in about 60% of cases. The bacteria that most commonly cause ear infections are:

- Streptococcus pneumoniae (also called S. pneumoniae or pneumococcus) is the most common bacterial cause of acute otitis media, causing about 40 - 80% of cases in the U.S.

- Haemophilus influenzae, the next most common culprit, is responsible for 20 - 30% of acute infections.

- Moraxellacatarrhalis is responsible for 10 - 20% of infections.

- Other bacteria include Streptococcus pyogenes and (rarely) Staphylococcus aureus.

Viruses. Viruses play an important role in many ear infections, and can set the scene for a bacterial infection. Rhinovirus is a common virus that causes a cold and plays a leading role in the development of ear infections. It is not the direct infecting organism, however. If a cold does occur, the virus can cause the membranes along the walls of the inner passages to swell and obstruct the airways. If this inflammation blocks the narrow Eustachian tube, the middle ear may not drain properly. Fluid builds up and becomes a breeding ground for bacteria and subsequent infection.

However, other viruses, such as respiratory syncytial virus (RSV, a virus responsible for childhood respiratory infections) and influenza (flu), can be the actual causes of some ear infections. Nearly a third of infants and toddlers with upper respiratory infections go on to develop acute otitis media.

Increasing evidence suggests that both viruses and bacteria play a role in ear infections. Viruses can increase middle ear inflammation and interfere with antibiotics' efficacy in treating bacterial-causes ear infections. HIV or other immunocompromised states also increase the risk for ear infections

Anatomic Abnormalities

Medical or Physical Conditions that Affect the Middle Ear. Any medical or physical condition that reduces the ear's defense system can increase the risk for ear infections. Children with shorter than normal and relatively horizontal Eustachian tubes are at particular risk for initial and recurrent infections. Congenital structural abnormalities, such as cleft palate, increase risk. Genetic conditions, such as Kartagener's syndrome in which the cilia (hair-like structures) in the ear are immobile and cause fluid build-up, also increase the risk. Children with Down syndrome or fetal alcohol syndrome may also be at increased risk due to anatomical abnormalities.

Otitis media with effusion (OME) may occur spontaneously following an episode of acute otitis media. Susceptibility to OME may also be due to an abnormal or malfunctioning Eustachian tube that causes a negative pressure in the middle ear, which allows fluid to leak in through capillaries.

Risk Factors

In the United States, ear infections are the most common reason why a child sees the doctor.

Age

Acute Otitis Media (AOM). About two-thirds of children will have a least one attack of AOM by age 3, and a third of these children will have at least three episodes. Boys are more likely to have infections than girls.

AOM generally affects children ages 6 - 18 months. The earlier a child has a first ear infection, the more susceptible they are to recurrent episodes (for instance, three or more episodes within a 6-month period).

As children grow, the structures in their ears enlarge and their immune systems become stronger. By 16 months, the risk for recurrent infections rapidly decreases. After age 5, most children have outgrown their susceptibility to any ear infections.

Otitis Media with Effusion. OME is very common in children age 6 months to 4 years, with about 90% of children having OME at some point. More than half of children have OME by age 2.

Other Risk Factors

Ear infections are more likely to occur in the fall and winter. The following conditions also put children at higher risk for ear infection:

- Allergies. Allergies can cause inflammation in the airways, which may contribute to ear infections. Allergies are also associated with asthma and sinusitis. However, a causal relationship between allergies and ear infections has not been definitively established.

- Enrollment in day care. Although ear infections themselves are not contagious, the respiratory infections that often precede them can pose a risk for children who have close and frequent exposure to other children in settings such as day care and school.

- Exposure to second-hand cigarette smoke. Parents who smoke significantly increase the risk that their children will develop middle ear infections.

- Bottle-feeding. Babies who are bottle-fed may have a higher risk for otitis media than breastfed babies. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends breastfeeding for at least the baby's first 6 months.

- Pacifier use. The use of pacifiers may place children at higher risk for ear infections. Sucking increases production of saliva, which helps bacteria travel up the Eustachian tubes to the middle ear.

- Obesity. Obesity has been associated with risk for OME.

- Having siblings with recurrent ear infections.

Complications

Hearing Loss and Speech or Developmental Delay

Severe cases of recurrent acute otitis media (AOM) or persistent otitis media with effusion (OME) may impair hearing for a period of time, but the hearing loss is not substantial or permanent for most children.

Hearing loss in children may temporarily slow down language development and reading skills. However, uncomplicated chronic middle ear effusion generally poses no danger for developmental delays in otherwise healthy children. As the majority of chronic ear effusion cases eventually clear up on their own, many doctors recommend against placement of tympanostomy tubes for most children.

Rarely, patients with chronic otitis media develop involvement of the inner ear. In these situations hearing loss can potentially be permanent. Most of these patients will also have problems with vertigo (dizziness).

Physical and Structural Injuries in the Face and Ears

Serious complications or permanent physical injuries from ear infections are very uncommon, but may include:

- Structural damage. Certain children with severe or recurrent otitis media may be at risk for structural damage in the ear, including erosion of the ear canal.

- Cholesteatomas. Inflammatory tissues in the ear called cholesteatomas are an uncommon complication of chronic or severe ear infections.

- Calcifications. In rare cases, even after a mild infection, some children develop calcification and hardening in the middle and, occasionally, in the inner ear. This may be due to immune abnormalities.

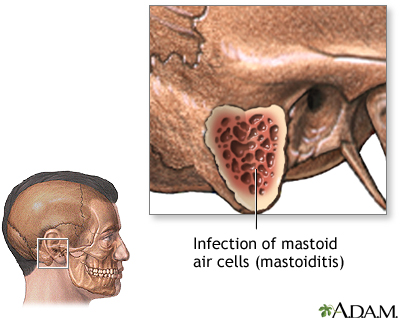

Mastoiditis

Before the introduction of antibiotics, mastoiditis (an infection in the bones located in the skull region behind the ears) was a serious, although rare, complication of otitis media. The condition is difficult to treat and requires intravenous antibiotics and drainage procedures. Surgery may be necessary.

If pain and fever persist in spite of antibiotic treatment of otitis media, the doctor should check for mastoiditis. Most cases of mastoiditis are generally not associated with ear infections.

Other Possible Complications

Meningitis. In rare cases, bacteria from a severe ear infection can spread to the tissues surrounding the brain.

Facial Paralysis. Very rarely, a child with acute otitis media may develop facial paralysis, which is temporary and usually relieved by antibiotics or possibly drainage surgery. Facial paralysis may also occur for patients with chronic otitis media and a cholesteatoma (tissue in the middle ear). Surgery is often necessary to correct this condition.

Symptoms

Symptoms of acute otitis media usually develop suddenly and can include:

- Pain or discomfort in the ear. However, it is difficult to determine if an infant or child who hasn't yet learned to speak has an ear infection. Some children may indicate pain if they have trouble swallowing food. Some parents believe that tugging on the ear indicates an infection, but this gesture is more likely to indicate pain from teething.

- Coughing

- Nasal congestion

- Fever

- Irritability

- Sleeplessness

- Loss of appetite

- Vomiting

- Diarrhea

- Listlessness

If the ear infection is severe, the tympanic membrane may rupture, causing the parent to notice pus draining from the ear. (This usually brings relief from pain.) Pus in the ear may cause hearing loss in some children.

Fevers and colds often make children irritable and fussy, so it is difficult to determine if acute otitis media is present as well. Symptoms are not apparent in about a third of children with acute middle ear infection.

Symptoms of Otitis Media with Effusion

OME may have no symptoms at all. Some hearing loss may occur, but it is often fluctuating and hard to detect, even by observant parents. The only sign to a parent that the condition exists may be when a child complains of "plugged up" hearing. Other symptoms can include loud talking, not responding to verbal commands, and turning up the television or radio.

Older children with OME may have difficulty targeting specific sounds in a noisy room. In such cases, some parents or teachers may attribute their behavior to lack of attention or even to an attention deficit disorder. Older children and adults may also notice a sense of fullness in the ear. OME is often diagnosed during a regular pediatric visit.

Diagnosis

The doctor should be sure to ask the parent if the child has had a recent cold, flu, or other respiratory infection. If the child complains of pain or has other symptoms of otitis media, such as redness and inflammation, the doctor should rule out any other causes. These may include:

- Otitis media with effusion. OME is commonly confused with acute otitis media. OME must be ruled out because it does not respond to antibiotics.

- Dental problems (such as teething).

- Infection in the outer ear. Symptoms include pain, redness, itching, and discharge. Infection in the outer ear, however, can be confirmed by tugging the outer ear, which will produce pain. (This movement will have no significant effect if the infection is in the middle ear.)

- Foreign objects in the ear. This can be dangerous. A doctor should always check for this first when a small child indicates pain or problems in the ear.

- Viral infection can produce redness and inflammation. Such infections, however, are not treatable with antibiotics and resolve on their own.

- A parent's or child's attempts to remove earwax.

- Intense crying can cause redness and inflammation in the ear.

Physical Examination

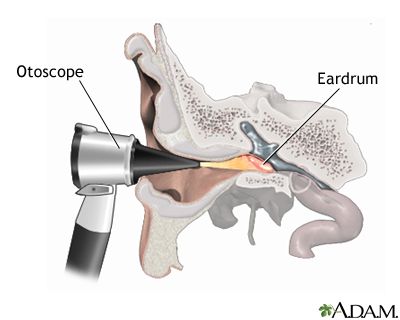

Instruments Used for Examining the Ear. An ear examination should be part of any routine physical examination in children, particularly because the problem is so common and may not cause symptoms.

- The doctor first removes any ear wax (called cerumen) in order to get a clear view of the middle ear.

- The doctor uses a small flashlight-like instrument called an otoscope to view the ear directly. This is the most important diagnostic step. The otoscope can reveal signs of acute otitis media, bulging eardrum, and blisters.

- To determine an ear infection, the doctor should use a pneumatic otoscope. This device detects any reduction in eardrum motion. It has a rubber bulb attachment that the doctor presses to push air into the ear. Pressing the bulb and observing the action of the air against the eardrum allows the doctor to gauge the eardrum's movement.

- Some doctors may use tympanometry to evaluate the ear. In this case, a small probe is held to the entrance of the ear canal and forms an airtight seal. While the air pressure is varied, a sound with a fixed tone is directed at the eardrum and its energy is measured. This device can detect fluid in the middle air and also obstruction in the Eustachian tube.

- A procedure similar to tympanometry, called reflectometry, also measures reflected sound. It can detect fluid and obstruction, but does not require an airtight seal at the canal.

Neither tympanometry nor reflectometry are substitutes for the pneumatic otoscope, which allows a direct view of the middle ear.

Findings Indicating AOM or OME. A diagnosis of AOM requires all three of the following criteria:

- History of recent sudden symptoms. Symptoms may include fever, pulling on the ear, pain, irritability, or discharge (otorrhea) from the ear.

- Presence of fluid in the middle ear. This may be indicated by fullness or bulging of the eardrum or limited mobility.

- Signs and symptoms of inflammation. These may include redness of the eardrum as well as assessment of the child's discomfort. Ear pain that is severe enough to interfere with sleep may indicate inflammation.

AOM (fluid and infection) is often difficult to differentiate from OME (fluid without infection). It is important for a doctor to make this distinction as OME does not require antibiotic treatment. In patients with OME, an air bubble may be visible and the eardrum is often cloudy and very immobile. A scarred, thick, or opaque eardrum may make it difficult for the doctor to distinguish between acute otitis media and OME.

Home Diagnosis

Parents can also use a sonar-like device, such as the EarCheck Monitor, to determine if there is fluid in their child's middle ear. EarCheck uses acoustic reflectometry technology, which bounces sound waves off the eardrum to assess mobility. When fluid is present behind the middle ear (a symptom of AOM and OME), the eardrum will not be as mobile. The device works like an ear thermometer and is painless. Results indicate the likelihood of the presence of fluid and may help patients decide whether they need to contact their child's doctor. However, it is not recommended that children be treated with antibiotics based on the findings using this device.

Tympanocentesis

On rare occasions the doctor may need to draw fluid from the ear using a needle for identifying specific bacteria, a procedure called tympanocentesis. This procedure can also relieve severe ear pain. It is most often performed by an ear, nose, and throat (ENT) specialist, and usually only in severe or recurrent cases. In most cases, tympanocentesis is not necessary in order to obtain an accurate enough diagnosis for effective treatment.

Determining Hearing Problems

Hearing tests performed by an audiologist are usually recommended for children with persistent otitis media with effusion. A hearing loss below 20 decibels usually indicates problems.

Determining Impaired Hearing in Infants and Small Children. Unfortunately, it is very difficult to test children under 2 years old for hearing problems. One way to determine hearing problems in infants is to gauge the baby's language development:

- At 4 - 6 weeks most babies with normal hearing make cooing sounds.

- By around 5 months, infants should be laughing out loud and making one-syllable sounds with both a vowel and consonant.

- Between 6 - 8 months, babies should be able to make word-like sounds with more than one syllable.

- Usually starting around 7 months, and by 10 months, babies babble (making many word-like noises).

- Around 10 months, babies can identify and use some term for a parent, such as dada, baba, or mama.

- Babies speak their first word usually by the end of their first year.

If a child's progress is significantly delayed beyond these times, a parent should suspect possible hearing problems.

Determining Impaired Hearing in Older Children. Hearing loss in older children may be detected by the following behaviors:

- Not responding to speech spoken beyond 3 feet away

- Difficulty following directions

- Limited vocabulary

- Social and behavioral problems

Prevention

The best way to prevent ear infections is to prevent colds and flu.

Good Hygiene. Colds and flus are spread primarily when an infected person coughs or sneezes near someone else. A very common method for transmitting a cold is by shaking hands. Everyone should always wash their hands before eating and after going outside. Ordinary soap is sufficient. Waterless hand cleaners that contain an alcohol-based gel are also effective for everyday use and may even kill cold viruses. (They are less effective, however, if extreme hygiene is required. In such cases, alcohol-based rinses are needed.) Antibacterial soaps add little protection, particularly against viruses. Wiping surfaces with a solution that contains 1 part bleach to 10 parts water is very effective in killing viruses.

Influenza ("Flu") Vaccine

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) recommend annual influenza vaccination for all children over 6 months of age. Preventing influenza (the "flu') may be a more important protective measure against ear infections than preventing bacterial infections. For example, studies report that children who are vaccinated against influenza experience a third fewer ear infections during flu season than unvaccinated children.

Flu Vaccines. Flu vaccines produce an immune response that attacks the active virus. Vaccines are typically given by injection, usually between October and December. Antibodies to the influenza virus generally develop within 2 weeks of vaccination, and immunity peaks within 4 - 6 weeks, then gradually wanes. An intranasal vaccine called FluMist is approved for children ages 2 years and older. FluMist is made from a live but weakened influenza virus; flu shots use inactivated (not live) viruses. Children younger than 2 years old, and children younger than age 5 who have asthma or recurrent wheezing, should not receive FluMist.

Possible side effects include:

- Allergic Reaction. Newer vaccines contain very little egg protein, but an allergic reaction still may occur in people with strong allergies to eggs.

- Soreness at the Injection Site. The influenza vaccine may cause redness or soreness at the injection site for 1 - 2 days afterward.

- Flu-like Symptoms. Other side effects include mild fatigue and muscle aches and pains. They tend to occur between 6 - 12 hours after the vaccination and last up to 2 days. These symptoms are not influenza itself but an immune response to the virus proteins in the vaccine. Anyone with a fever, however, should not be vaccinated until the ailment has subsided.

Antiviral Drugs. Antiviral drugs are available to treat influenza. One such drug, oseltamivir (Tamiflu), is approved for use in children age 1 year and older. Some studies report it can significantly help prevent ear infections. Another antiviral drug, zanamivir (Relenza), is available for children older than age 7 years.

Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine

The pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) protects against S. pneumoniae (also called pneumococcal) bacteria in children, the most common cause of middle ear infections, pneumonia, and other respiratory infections. A new type of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, Prevnar 13, protects against more strains of disease-causing bacteria than the older version. It is specifically approved to help prevent invasive pneumococcal disease and otitis media. The recommended schedule of pneumococcal immunization is four doses, one given at 2, 4, 6, and 12 - 15 months of age.

Dietary Factors and Supplements

Healthy Diet. Daily diets should include foods such as fresh, dark-colored fruits and vegetables, which are rich in antioxidants and other important food chemicals that may help boost the immune system.

Probiotics ("Good" Bacteria). Researchers are studying the possible protective value of certain strains of lactobacilli, bacteria found in the intestines. Some of these strains, particularly acidophilus, are used to make yogurt. Studies have been mixed on probiotics’ benefits for preventing ear infections.

Avoiding Exposure to Cigarette Smoke

No one should smoke around children. Several studies have found that children who live with smokers have a significantly increased risk for ear infections.

Breastfeeding

Breastfeeding offers protection against many early infections, including ear infections. Mother's milk provides immune factors that help protect the child from infections. Also, infants are held during breastfeeding in a position that allows the Eustachian tubes to function well.

If possible, new mothers should breastfeed their infants for at least 4 - 6 months. According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, exclusively breastfeeding for a baby’s first 6 months helps to prevent ear and other respiratory infections. For bottle-fed babies, to improve protection mothers should not lay babies down with their bottle; they should hold the infants in the same way they would to breastfeed them.

Treatment

Many of the treatments for ear infections, particularly antibiotic use and surgical procedures, are often unnecessary. Between 80 - 90% of all children with uncomplicated ear infections recover within a week without antibiotics. Likewise, receiving antibiotics for an acute ear infection does not seem to prevent children from having fluid behind the ears after the infection is cleared up. Antibiotics are rarely recommended for otitis media with effusion. In addition, the overuse of antibiotics has led a serious problem of bacterial strains that are resistant to common antibiotics.

Antibiotics are necessary for treatment of some children with acute otitis media, particularly those who are younger than age 6 months.

Treatment Guidelines for Acute Otis Media (AOM)

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) guidelines and recent evidence support the following recommendations:

- Accurate diagnosis of AOM including differentiation from OME.

- Children younger than 6 months of age should receive immediate antibiotic treatment.

- Children 6 months or older should be treated for pain within the first 24 hours with either acetaminophen (Tylenol, generic) or ibuprofen (Advil, generic).

- An initial observation period of 48 - 72 hours ("watchful waiting") is recommended for select children to determine if the infection will resolve on its own without antibiotic treatment. (Most children do improve within 72 hours.)

- For children aged 6 months - 2 years, criteria for recommending an observation period are an uncertain diagnosis of AOM and a determination that the AOM is not severe. For children older than 2 years, the observation period criteria are non-severe symptoms or uncertain diagnosis. Severe AOM symptoms include moderate to severe pain and a fever of at least 102.2 °F (39 °C).

- Preventive antibiotics (antibiotic prophylaxis) may be recommended for recurrent acute otitis media. Which children should be treated this way, as well as which antibiotics and for how long, have not been clearly determined.

Treatment Guidelines for Otitis Media with Effusion (OME)

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), and the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS) clinical practice guidelines for OME recommend the following treatments:

Watchful Waiting for OME. The child is typically monitored for the first 3 months. Antibiotics are not helpful for most patients with OME. The condition resolves without treatment in nearly all children, especially those whose OME followed an acute ear infection. About 75 - 90% of OME cases that result from AOM resolve within 3 months. If OME lasts longer than 3 months, a hearing test should be conducted. Even if OME lasts for longer than 3 months, the condition generally resolves on its own without any long-term effects on language or development, and intervention may not be necessary. The doctor will re-evaluate the child at periodic intervals to determine if there is risk for hearing loss.

Drug Treatment. It is important for parents to recognize that persistent fluid behind the eardrum after treatment for acute otitis media does not indicate failed treatment. Antibiotics, decongestants, antihistamines and corticosteroids do not help and are not recommended for routine management of OME. These drugs are not effective for OME, either when used alone or in combination. Antihistamines and decongestants may cause more harm than good by provoking side effects such as stomach upset and drowsiness. At present, there is no compelling evidence that allergy treatment helps with OME management nor has a causal relationship between allergies and OME been established.

Surgery. The decision to pursue surgery must be determined on an individual basis. Ear tube insertion may be recommended when fluid builds up behind your child's eardrum and does not go away after 4 months or longer. Fluid buildup may cause some hearing loss while it is present. But most children do not have long-term damage to their hearing or their ability to speak even when the fluid remains for many months.

Children with OME lasting longer than 4 months may be candidates for surgery if they have:

- Hearing loss greater than 40 dB

- Hearing loss between 21 - 39 dB (Children in this group may be observed or considered for surgery.)

- Hearing loss of 20 dB or less, when speech, language, or developmental problems are observed

- OME and structural damage to the ear canal, eardrum, or middle ear

Tympanostomy (the insertion of tubes into the eardrum) is the first choice for surgical intervention. Adenoidectomy (removal of adenoids) plus myringotomy (removal of fluid), with or without tube insertion, is sometimes recommended as a repeat surgical procedure. (Myringotomy alone is not recommended for OME treatment. Between 20 - 50% of children who undergo this procedure may have OME relapse and need additional surgery). Tube insertion may be advised for children younger than 4 years of age. Adenoidectomy is not recommended as an initial procedure unless some other condition (chronic sinusitis, nasal obstruction, adenoiditis) is present.

Tonsillectomy (removal of tonsils) is not recommended for OME treatment.

Home Remedies

Careful monitoring of the child's condition (watchful waiting) along with home remedies may be a viable alternative to antibiotic treatment for many children with a first episode of acute otitis media. However, in some situations parents should contact their medical professional immediately:

- Seek immediate medical attention for high fever, severe pain, or other signs of complications.

- Parents of infants should contact their doctor immediately if they have any fever, regardless other symptoms.

Natural Remedies for Ear Aches

Before antibiotics, parents used home remedies to treat the pain of ear infections. Now, with current concern over antibiotic overuse, many of these remedies are again popular.

- Parents can press a warm water bottle or warm bag of salt against the ear. Such old-fashioned remedies may help to ease ear pain.

- Due to the high risk of burns, ear candles should not be used to remove wax from ears. These candles are not safe or effective for treatment of AOM or other ear conditions.

Herbal remedies are not standardized or regulated, and their quality and safety are largely unknown. Parents should never give their child herbal remedies, including oral remedies, without approval from a doctor.

Valsalva's Maneuver. A simple technique called the Valsalva's maneuver is useful in opening the Eustachian tubes and providing occasional relief from the chronic stuffy feeling that accompanies otitis media with effusion. It may also be useful for unplugging ears during air travel descent. It works as follows:

- The child takes a deep breath and closes the mouth.

- The child then blows the nose gently while, at the same time, pinching it firmly shut.

- The parent should be sure to instruct the child not to blow too hard or the eardrum could be harmed.

Do not use this technique if an infection is present.

Pain Relievers

A number of pain relievers are available to help relieve symptoms.

- Either acetaminophen (Tylenol, generic) or ibuprofen (Advil, generic) is the pain reliever of choice for children.

- Older children may be able to take prescription pain relievers that contain codeine if the pain is severe.

- Eardrops containing anesthetics are also available by prescription. They provide short-acting pain relief and may help children endure ear discomfort until an oral pain reliever takes effect. Parents should check with a doctor before using them. Eardrops could cause damage in children who have a ruptured eardrum. This might be indicated by fluid drainage from the ear canal.

Note: Aspirin and aspirin-containing products are not recommended for children or adolescents. Reye syndrome, a very serious condition, is associated with aspirin use in children who have chickenpox or flu.

Cold and Allergy Remedies

Many non-prescription products are available that combine antihistamines, decongestants, and other ingredients, and some are advertised as cold remedies for children. Researchers have found little or no benefits for acute otitis media or for otitis media with effusion using decongestants (either oral or nasal sprays or drops), antihistamines, or combination products. Their use is not recommended for AOM or OME.

Recent research has questioned the general safety of cough and cold products for children. They are currently banned for use in children under age 4 years. The American College of Chest Physicians recommends against the use of nonprescription cough and cold medicines in children age 14 years and younger.

Precautions when Swimming

Swimming can pose specific risks for children with current ear infections or previous surgery. Water pollutants or chemicals may exacerbate the infection, and underwater swimming causes pressure changes that can cause pain. The following precautions should be taken:

- Children with ruptured acute otitis media (drainage from ear canal) should not go swimming until their infections are completely cured.

- Children with AOM that is not ruptured should not dive or swim underwater.

- Some doctors recommend that children with implanted ear tubes should use earplugs or cotton balls coated in petroleum jelly when swimming to prevent infection. Others say earplugs are only necessary if the child will be diving underwater. Parents should consult their child's doctor.

Medications

Antibiotic Regimens for Acute Otitis Media

Most children with uncomplicated acute otitis media (AOM) will recover fully without antibiotic therapy. When antibiotics are needed, a number of different drug classes are available for treating acute ear infections. Amoxicillin is a penicillin antibiotic and the drug of first choice. Other antibiotics are available for children who are allergic to penicillin or who do not respond within 2 - 3 days.

Duration. If a child needs antibiotics for acute otitis media, the drugs should be taken for the following periods of time:

- A 10-day course of antibiotics is usually recommended for children younger than 6 years of age, and for those with severe AOM.

- Antibiotic therapy for 5 - 7 days is recommended for children 6 years of age or older with mild-to-moderate symptoms.

Parents should be sure their child finishes the entire course of therapy. Failure to finish is a major factor in the growth of bacterial strains that are resistant to antibiotics.

What to Expect. Earaches usually resolve within 24 hours after taking an antibiotic, although about 10% of children who are treated do not respond. This may occur when a virus is present or if the bacteria causing the ear infection is resistant to the prescribed antibiotic. A different antibiotic may be needed.

In some children whose treatment is successful, fluid will still remain in the middle ear for weeks or months, even after the infection has resolved. During that period, children may have some hearing problems, but eventually the fluid almost always drains away. Antibiotics should not be used to treat residual fluid.

Follow-Up. Your child should return to the doctor's office:

- Two to 3 weeks after therapy, if initial therapy cleared up the infection and the child is less than 15 months old or has risk factors for reinfection

- Three to 6 weeks after treatment, if initial therapy cleared up the infection and the child is older than 15 months old and has no specific risk factors

- Within 48 hours of taking the last antibiotic dose if signs of infection are still present (for example, there is still pus in the ear)

When suspecting complications, consult with an ear, nose, and throat specialist (otolaryngologist). This specialist may perform a tympanocentesis or myringotomy procedure in which fluid is drawn from the ear and examined for specific organisms. But, this is reserved for severe cases.

Specific Antibiotics Used for Acute Otitis Media

The selection of an antibiotic is determined in part by the severity of the child's condition as well as a history of response/non-response to antibiotic therapy. Treatment decisions take into account whether the child's condition is severe or non-severe.

Amoxicillin is generally recommended for first-line treatment of AOM. The combination drug amoxicillin-clavunate may be prescribed for patients who have severe pain or a fever higher than 102.2 °F (39 °C). Other drug classes may be prescribed if a child is allergic to penicillin or does not respond to the initial therapy.

The following treatment guidelines provide general recommendations based on the severity of a child's AOM.

First-line treatment for non-severe AOM:

- Amoxicillin 80 - 90 mg/kg per day orally. Amoxicillin is a penicillin antibiotic.

If the patient has an allergy or a history of non-response to penicillin drugs, one of the following antibiotics may be prescribed instead:

- Azithromycin or clarithromycin. These drugs are in the macrolide class and are taken by mouth.

- Cefdinir, cefuroxime, or cefpodoxime. These drugs, classified as cephalosporins, are taken by mouth. They may cause reactions in penicillin-allergic patients.

If the patient does not respond to amoxicillin or alternative antibiotic drugs after 48 - 72 hours, one of the following drugs may be prescribed:

- Amoxicillin-clavulanate or ceftriaxone. Ceftriaxone is injected intramuscularly. The other drug is administered orally. Each of these drugs is a different type of antibiotic. Amoxicillin-clavulanate (Augmentin, generic) is classified as a penicillin. Ceftriaxone (Rocephin, generic) is a cephalosporin.

First-line treatment for severe AOM:

- Amoxicillin-clavulanate (Augmentin, generic). This antibiotic is known as an augmented penicillin. It works against a wide spectrum of bacteria and is administered orally.

Second-line treatment for severe AOM:

- Ceftriaxone. Ceftriaxone (Rocephin, generic) is an injectable cephalosporin that may be prescribed as an alternative to amoxicillin-clavulanate, especially for children who have vomiting or other conditions that hamper oral administration.

- Tympanocentesis. Patients with severe AOM who fail to respond to amoxicillin-clavulanate after 48 - 72 hours may require the withdrawal of fluid from the ear (tympanocentesis) in order to identify the bacterial strain causing the infection.

Side Effects of Antibiotics

- The most common side effects of nearly all antibiotics are gastrointestinal problems, including cramps, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. This can be a significant problem in infants and small children.

- Tetracycline use during pregnancy, infancy, and childhood may lead to enamel defects and discolorations of permanent teeth.

- Allergic reactions can occur with all antibiotics but are most common with medications derived from penicillin or sulfa. These reactions can range from mild skin rashes to rare but severe, even life-threatening, anaphylactic shock.

- Some drugs, including certain over-the-counter medications, interact with antibiotics. Parents should tell the doctor about all medications their child is taking.

Surgery

Tympanostomy (with Myringotomy)

A tympanostomy involves the insertion of tubes to allow fluid to drain from the middle ear. The procedure involves:

- A general anesthetic (asleep, no pain). Children typically recover completely within a few hours.

- Myringotomy (removal of fluid) is performed first.

- After myringotomy, the doctor inserts a tube to allow continuous drainage of the fluid from the middle ear.

Postoperative Effects. Tympanostomy is a simple procedure, and the child almost never has to spend the night in the hospital. Acetaminophen (Tylenol, generic) or ibuprofen (Advil, generic) is sufficient for any postoperative pain in most children. Some children, however, may need codeine or other powerful pain relievers.

Generally, the tubes stay in the eardrum for at least several months before coming out on their own. On rare occasions, they will need to be surgically removed.

Complications. Otorrhea, drainage of secretion from the ear, is the most common complication after surgery and can be persistent in some children. It is usually treated with antibiotic eardrops.

More serious complications from the operation are very uncommon but may include:

- General anesthetic risks. Rarely, allergic reactions or other complications, such as throat spasm or obstruction, may occur. The risk is highest in children who have other medical conditions, most commonly upper respiratory infections, lung disease, or gastroesophageal reflux disorder (GERD). Anesthetic-related risks are nearly always easily treated.

- Tube blockage. Sometimes the tubes become blocked from sticky secretions or clotted blood after the operation.

- Persistent eardrum perforation. This condition occurs when the eardrum does not close after the tubes have come out. It is the most common serious complication, but it is very rare.

- Scarring can also occur, particularly in children who need more than one procedure, but it almost never affects hearing.

- Cholesteatomas, small cyst-like masses filled with keratin (skin cells), develop around the tube site in about 1% of patients.

Success Rates. Hearing is almost always restored following tympanostomy. Failure to achieve normal or near-normal hearing is usually due to complicated conditions, such as preexisting ear problems or persistent OME in children who have had previous multiple tympanostomies. Persistent fluid is the main reason for continued impaired hearing. Only a small percentage of hearing loss cases can be attributed to complications of the operation itself.

Earplugs as a Precaution. Many doctors feel that children should use earplugs when swimming while the tubes are in place in order to prevent infection. Others feel that as long as the child does not dive or swim underwater, earplugs may not be necessary. Parents should talk to their child's doctor about this subject. Cotton balls coated with petroleum jelly are effective alternatives to ear plugs. Children do not need to wear earplugs while showering.

Follow-Up. Eventually, the tubes fall out as the hole in the eardrum closes. This may happen after several months or more than a year later. It is painless. In fact, the patient and parents may not even be aware that the tubes are out.

About 20 - 50% of children may have OME relapse and need additional surgery that involves adenoidectomy and myringotomy. Tube reinsertion may be recommended for children younger than 4 years of age.

Myringotomy

Myringotomy is used to drain the fluid and may be used (with or without ear tube insertion) in combination with adenoidectomy as a repeat surgical procedure if initial tympanostomy is not successful. It is not effective as a sole surgical procedure. Myringotomy involves the following steps:

- The surgeon makes a very small incision in the eardrum.

- Fluid is sucked out using a vacuum-like device.

- The fluid is usually examined for identifying specific bacteria.

- The eardrum heals in about a week.

Adenoid Removal

Adenoids are collections of spongy lymph tissue in the back of the throat, similar to the tonsils. Removal of the adenoids, called adenoidectomy, is usually considered only for OME if a pre-existing condition exists, such as chronic sinusitis, nasal obstruction, or chronic adenoiditis (inflammation of the adenoids). Unless these conditions exist, adenoidectomy is not recommended for treatment of OME.

Adenoidectomy plus myringotomy (removal of fluid) may be performed if an initial tympanostomy (tube insertion) procedure is unsuccessful in resolving OME. This combination procedure works best in children ages 4 years or older. Tube insertion alone is recommended for children under 4 years of age. It is not necessary to perform an adenoidectomy along with tube insertion for children under 4 years of age.

Laser-Assisted Myringotomy

Laser-assisted myringotomy is a technique that is being investigated as an alternative to conventional tympanostomy and myringotomy. At present, there is not enough evidence to say whether it is as good as ear tubes, the standard procedure. Some clinical trials have suggested that the success rate for laser-assisted myringotomy is half that of standard tympanostomy/myringotomy. Many insurance companies consider laser-assisted myringotomy to be an investigational procedure and will not pay for it.

Resources

- www.nidcd.nih.gov -- National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders

- www.aap.org -- American Academy of Pediatrics

- www.entnet.org -- American Academy of Otolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery

References

Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Licensure of a 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) and recommendations for use among children. MMWR. 2010 Mar 12;59(09):258-261.

American Academy of Family Physicians; American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery; American Academy of Pediatrics Subcommittee on Otitis Media With Effusion. Otitis media with effusion. Pediatrics. 2004 May;113(5):1412-29.

American Academy of Pediatrics Subcommittee on Management of Acute Otitis Media. Diagnosis and management of acute otitis media. Pediatrics. 2004 May;113(5):1451-65.

Coker TR, Chan LS, Newberry SJ, Limbos MA, Suttorp MJ, Shekelle PG, et al. Diagnosis, microbial epidemiology, and antibiotic treatment of acute otitis media in children: a systematic review. JAMA. 2010 Nov 17;304(19):2161-9.

Coleman C, Moore M. Decongestants and antihistamines for acute otitis media in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008 Jul 16;(3):CD001727.

Committee on Infectious Diseases. Policy statement -- Recommended childhood and adolescent immunization schedules -- United States, 2010. Pediatrics. 2010 Jan;125(1):195-6.

Griffin G, Flynn CA. Antihistamines and/or decongestants for otitis media with effusion (OME) in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011 Sep 7;(9):CD003423.

Hoberman A, Paradise JL, Rockette HE, Shaikh N, Wald ER, Kearney DH, et al. Treatment of acute otitis media in children under 2 years of age. N Engl J Med. 2011 Jan 13;364(2):105-15.

Jones LL, Hassanien A, Cook DG, Britton J, Leonardi-Bee J. Parental smoking and the risk of middle ear disease in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012 Jan;166(1):18-27. Epub 2011 Sep 5.

Koopman L, Hoes AW, Glasziou PP, Cees L, Appelman L, Burke P, et al. Antibiotic therapy to prevent the development of asymptomatic middle ear effusion in children with acute otitis media: a meta-analysis of individual patient data. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. Feb 2008;134(2):128-132.

Little P. Delayed prescribing -- a sensible approach to the management of acute otitis media. JAMA. 2006 Sep 13;296(10):1290-1.

Morris PS. Upper respiratory tract infections (including otitis media). Pediatr Clin North Am. 2009 Feb;56(1):101-17, x.

Morris PS, Leach AJ. Acute and chronic otitis media. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2009 Dec;56(6):1383-99.

Paradise JL, Feldman HM, Campbell TF, Dollaghan CA, Rockette HE, Pitcairn DL, et al. Tympanostomy tubes and developmental outcomes at 9 to 11 years of age. N Engl J Med. 2007 Jan 18;356(3):248-61.

Ramakrishnan K, Sparks RA, Berryhill WE. Diagnosis and treatment of otitis media. Am Fam Physician. 2007 Dec 1;76(11):1650-8.

Rosenfeld RM, Brown L, Cannon CR, Dolor RJ, Ganiats TG, Hannley M, et al. Clinical practice guideline: acute otitis externa. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006 Apr;134(4 Suppl):S4-23.

Rovers MM, Glasziou P, Appelman CL, Burke P, McCormick DP, Damoiseaux RA, et al. Antibiotics for acute otitis media: a meta-analysis with individual patient data. Lancet. 2006 Oct 21;368(9545):1429-35.

Smith JA, Danner CJ. Complications of chronic otitis media and cholesteatoma. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2006 Dec;39(6):1237-55.

Spiro DM, Tay KY, Arnold DH, Dziura JD, Baker MD, Shapiro ED. Wait-and-see prescription for the treatment of acute otitis media: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006 Sep 13;296(10):1235-41.

Tähtinen PA, Laine MK, Huovinen P, Jalava J, Ruuskanen O, Ruohola A. A placebo-controlled trial of antimicrobial treatment for acute otitis media. N Engl J Med. 2011 Jan 13;364(2):116-26.

|

Review Date:

5/31/2012 Reviewed By: Harvey Simon, MD, Editor-in-Chief, Associate Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School; Physician, Massachusetts General Hospital. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, A.D.A.M., Inc. |